What is "The Context Aggregator" about?

This article challenges Aggregation Theory's application to AI agents. The thesis: verification is domain-specific (legal has citations, code has tests, but "is this strategy memo good?" has no objective answer). This breaks the aggregation dynamic. Instead of one winner capturing the context layer, the market fragments into vertical city-states—an archipelago, not a skyline.

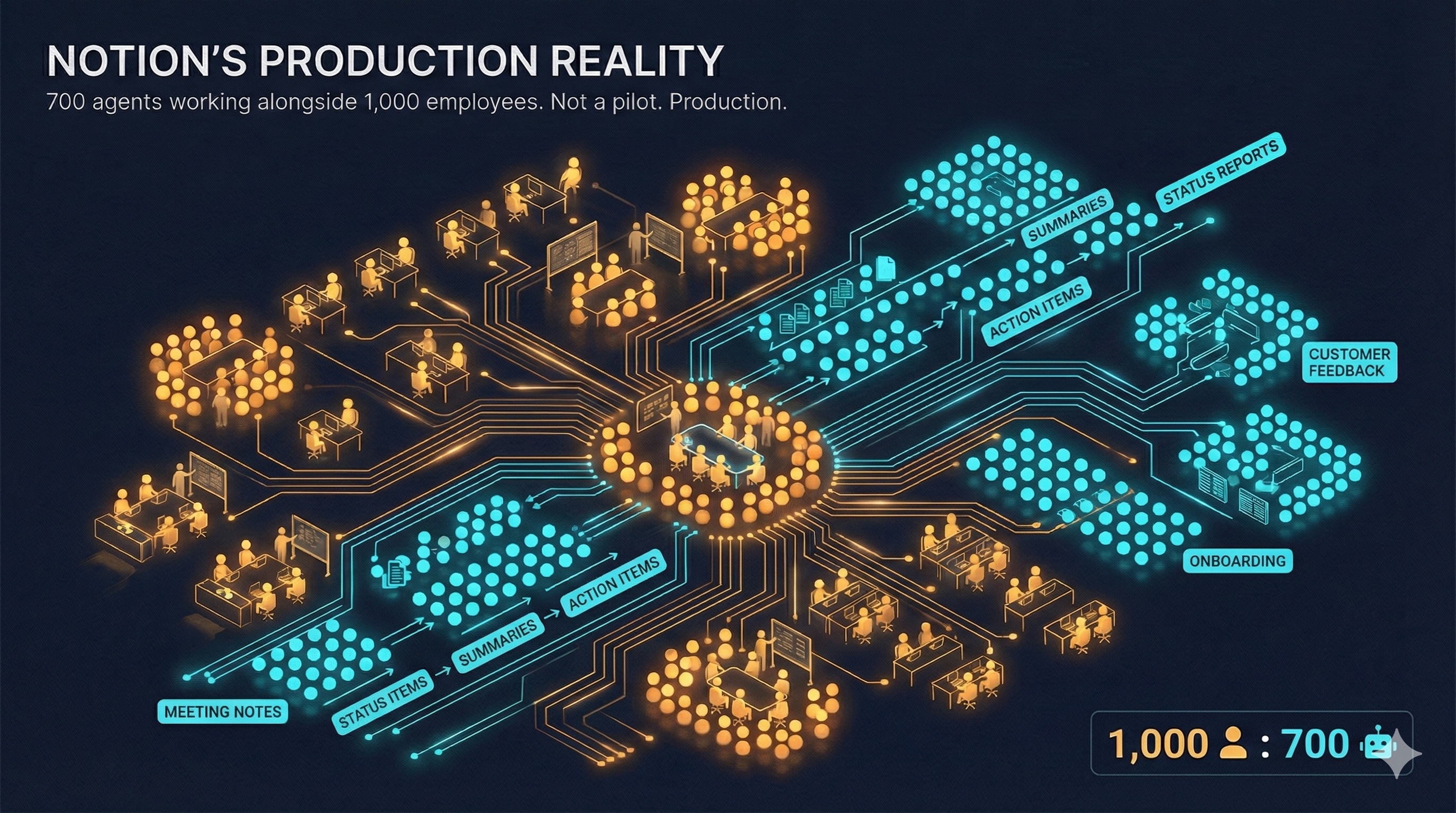

Ivan Zhao dropped a number recently that deserves more attention than it received.

In a long-form post titled "Steam, Steel, and Infinite Minds," the Notion CEO revealed that his company now runs 700 AI agents alongside 1,000 employees. Not a pilot program. Not an experiment. Production workloads: meeting notes, IT requests, customer feedback, onboarding, status reports.

This is what the "AI transformation" actually looks like when it arrives. And it points to who wins the next platform war.

The Rearview Mirror Problem

Zhao opens with Marshall McLuhan's observation that we always "drive into the future via the rearview mirror." Early phone calls were terse like telegrams. Early movies looked like filmed stage plays. Early AI looks like Google search boxes.

”"We're now deep in that uncomfortable transition phase which happens with every new technology shift."

This is exactly right. The chatbot interface—a text box that returns a response—is a skeuomorph. It's the telegram-style phone call. It's the filmed play. It works, but it misses what the new medium makes possible.

Zhao calls this the "waterwheel phase." When steam engines first arrived, factory owners swapped out waterwheels but kept everything else the same. Productivity gains were modest. The real breakthrough came when they realized they could decouple from water entirely—build factories anywhere, redesign the production floor around the new power source.

We're still bolting chatbots onto workflows designed for humans. We haven't yet reimagined what work looks like when the old constraints dissolve.

The Two Blockers

Zhao identifies why coding agents work while knowledge work agents struggle. This is the most important part of his essay:

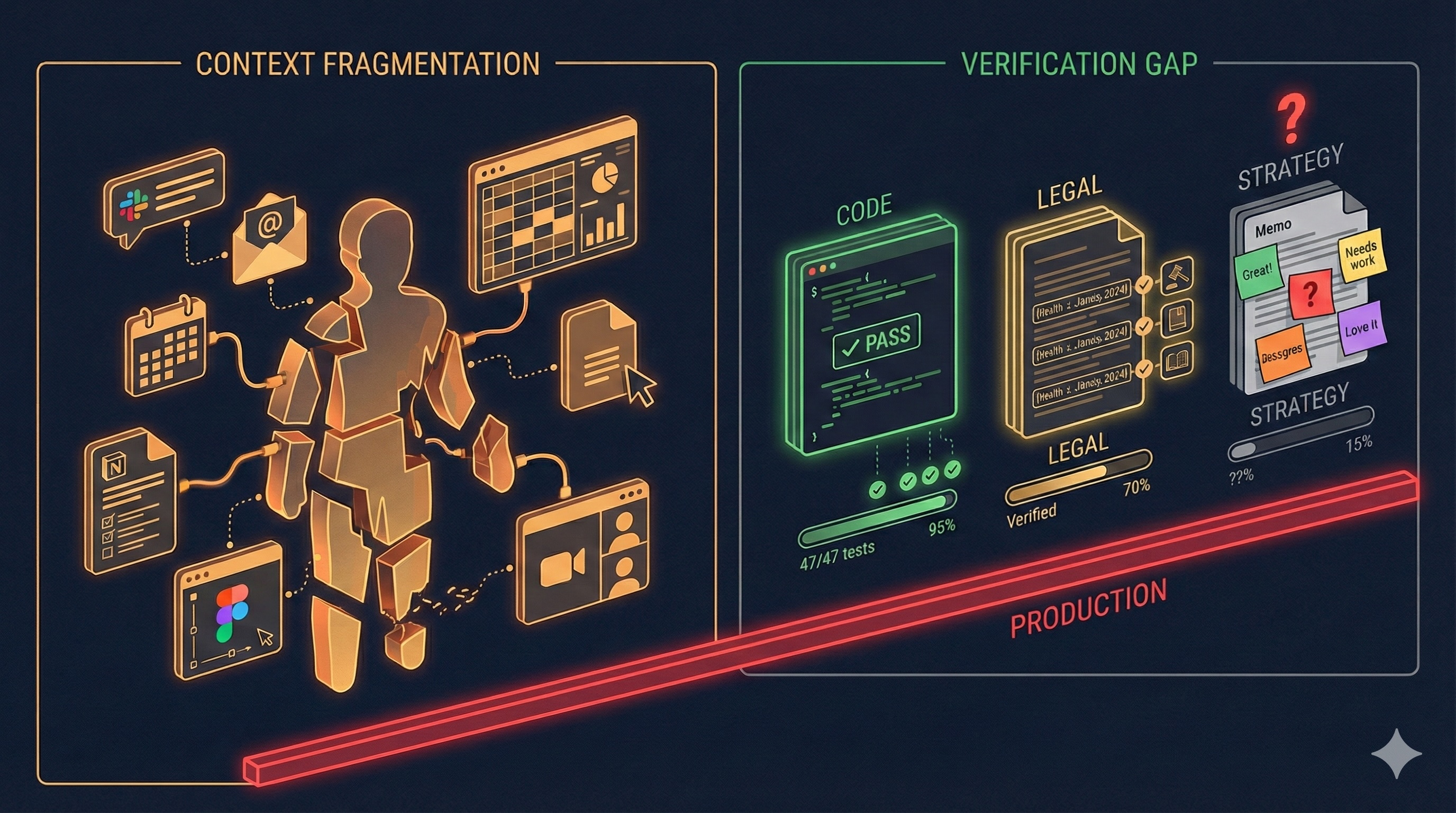

First, context fragmentation. For programmers, tools and context live in one place: the IDE, the repo, the terminal. But general knowledge work is scattered across dozens of tools. An AI agent trying to draft a product brief needs Slack threads, strategy docs, last quarter's metrics, and institutional memory that lives only in someone's head.

”"Today, humans are the glue, stitching all that together with copy-paste and switching between browser tabs."

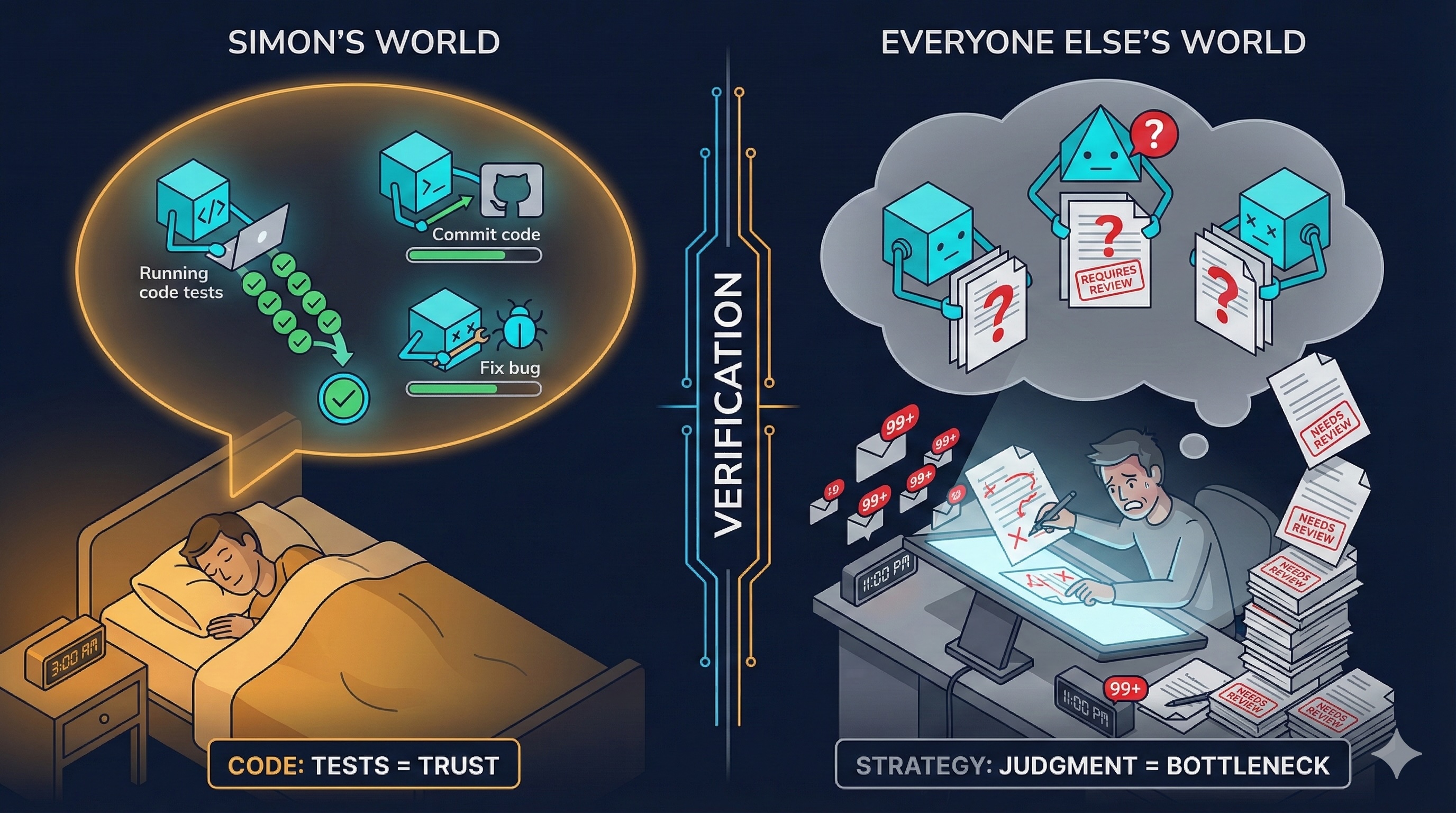

Second, verifiability. Code has a magical property: you can verify it with tests and errors. This lets model makers use reinforcement learning to improve coding agents. But how do you verify if a project is managed well? How do you test whether a strategy memo is good? This is the core thesis of Verification Determines Territory—domains with objective measurement see clear winners; domains with subjective judgment remain contested.

”"We haven't yet found ways to improve models for general knowledge work. So humans still need to be in the loop to supervise, guide, and show what good looks like."

This framing clarifies something important. The bottleneck to AI agent adoption isn't model capability. GPT-4, Claude, Gemini—they're all capable enough. The bottleneck is data architecture. Context is fragmented. Verification is missing. These are structural problems, not intelligence problems.

For a deeper dive on the context fragmentation problem, see The Context Crisis. For why verification matters, see Building Agent Evals.

Aggregation Theory Applied

To understand who wins here, it helps to apply Aggregation Theory.

New to Aggregation Theory? Ben Thompson's framework explains how platforms like Google and Facebook captured their markets. The short version: whoever "aggregates" the demand side (users) can commoditize the supply side (websites, content creators) and extract value from both. The aggregator wins by owning the customer relationship. Read the full theory →

In the classic formulation: platforms that aggregate supply and commoditize it capture value from both sides. Google aggregated websites, commoditized their content, and captured the search relationship. Facebook aggregated social connections, commoditized the social graph, and captured attention. In both cases, the aggregator owned the demand-side relationship while suppliers competed for access.

Applied to AI agents:

- Supply side: LLMs. These are commoditizing rapidly. GPT-4, Claude, Gemini—functionally equivalent for most tasks, competing on price and speed.

- Demand side: Knowledge workers. Fragmented across tools, workflows paced by meetings and email.

- Aggregation point: The context layer.

Whoever consolidates fragmented knowledge work context owns the agent value chain.

This is why Notion matters. Zhao isn't just building AI features—he's building the context aggregation layer. If your documents, wikis, databases, and workflows all live in Notion, then Notion has the unified context that agents need to operate. The 700 agents aren't a product feature. They're the strategy.

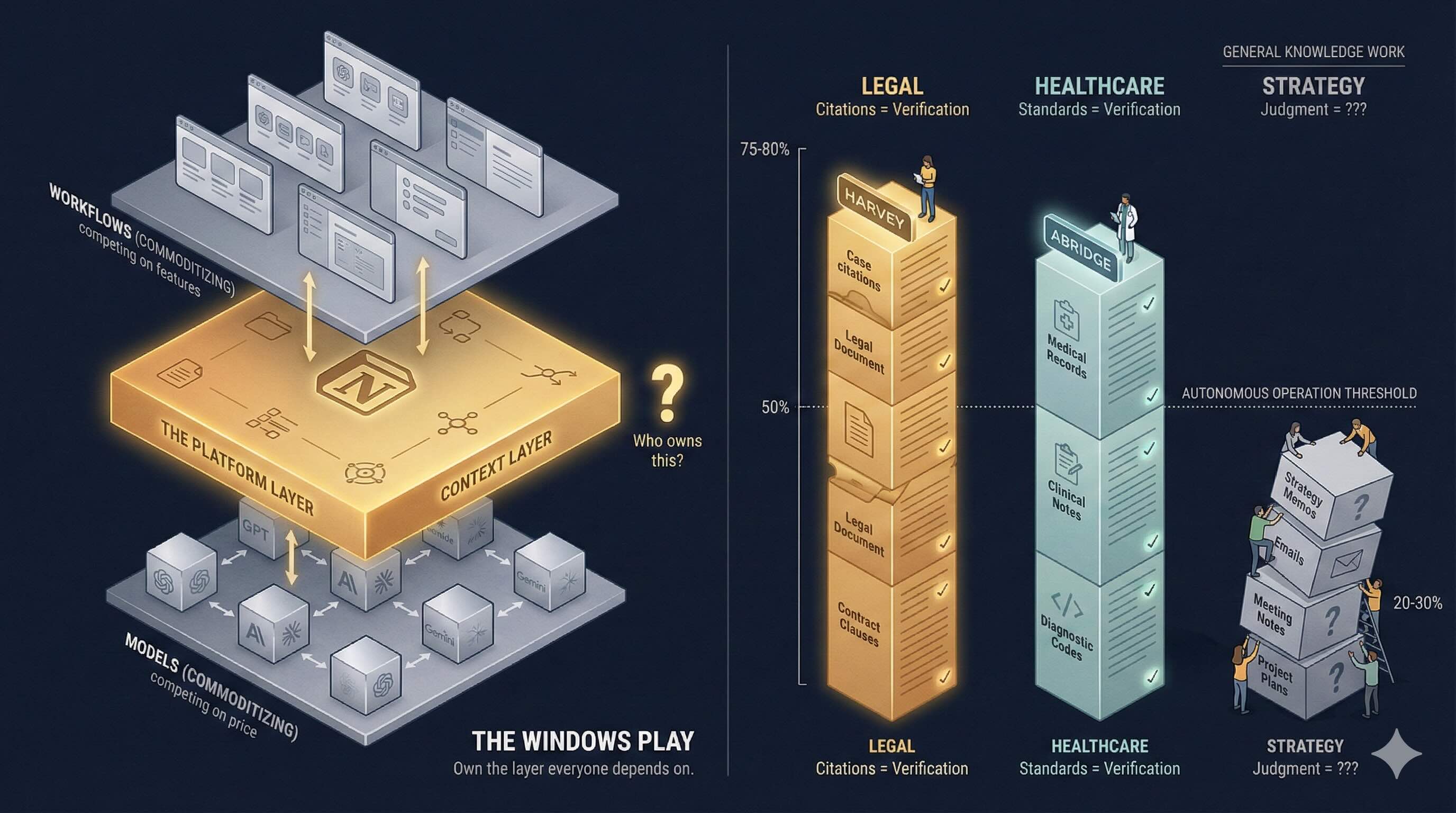

The Windows Play

Zhao is making what Thompson would call "the Windows Play": become the platform layer that both hardware (models) and software (workflows) depend on.

In the PC era, Windows owned the platform layer between Intel chips and application software. Chips commoditized—Intel competed with AMD on price. Applications commoditized—Word competed with WordPerfect on features. But Windows captured the value because both sides needed Windows to reach each other. Microsoft didn't need the best chips or the best apps. They needed to be the layer everyone depended on.

Notion's bet: own the document layer, own the context, own the agent value chain. Models become commoditized suppliers. Workflows become applications that run on Notion's context substrate.

The structural advantage: If you're already a Notion customer, the switching cost to adopt Notion's agents is zero. If you're using a competing agent platform, you have to solve context fragmentation yourself—which means building integrations with every tool your company uses.

This is the same bundle economics that let Microsoft Teams defeat Slack. Teams isn't better than Slack. Teams is free for anyone who already pays for Office. Notion's agents aren't necessarily better than standalone agents. They're native for anyone whose context already lives in Notion.

The Vertical Counter-Argument

There is, however, a case to be made that horizontal aggregation won't work for agents.

Consider Harvey AI. Harvey isn't trying to be the context layer for all knowledge work. Harvey is the context layer for legal knowledge work—and only legal knowledge work.

This narrowness is strategic. Harvey can solve both of Zhao's blockers within a single domain:

Context fragmentation: Legal work happens in a defined set of systems—document management, case law databases, firm precedents. Harvey integrates with all of them. The context consolidation problem is bounded.

Verifiability: Legal work has verification mechanisms. Citations can be checked against case law. Contract terms can be validated against playbooks. Harvey's 0.2% hallucination rate isn't magic—it's the result of domain-specific verification loops that don't exist for general knowledge work.

For why legal AI is structurally different, see The Legal AI Exception.

The vertical agent thesis argues that this pattern repeats across industries. Abridge for healthcare. Specialized agents for finance, accounting, HR. Each vertical can solve fragmentation and verification within its domain. Horizontal platforms cannot.

The Structural Question

The question, then, is not whether Notion or Harvey wins. It's whether horizontal aggregation can work at all when verticals capture the verification loop.

Zhao's own framing suggests the challenge. He notes that his co-founder Simon—a programmer—went from "10x" to "30-40x" by orchestrating multiple coding agents. Simon queues tasks before bed, letting agents work while he sleeps.

”"He's become a manager of infinite minds."

But Simon is a programmer. Coding has verification. The agents can run unsupervised because their outputs can be tested.

For Notion's 700 agents handling meeting notes and status reports, verification is human judgment. Someone has to review. Someone has to "show what good looks like." The Red Flag Act problem that Zhao references—a human walking in front of every car—may be unavoidable for knowledge work that lacks intrinsic verification.

This is the vertical advantage. Harvey can remove humans from the loop for citation-grounded legal research because citations are verifiable. Notion cannot remove humans from the loop for strategy memo drafting because quality is subjective. The ceiling for horizontal agent leverage is structurally lower.

The Steel Frame Implications

Zhao's "AI is steel for organizations" metaphor deserves extension.

Steel didn't just make buildings taller. It made new building types possible. Before steel, buildings topped out at six or seven floors—iron was too heavy and brittle to go higher. Steel frames could be lighter, walls thinner. Skyscrapers, factories, bridges—entirely new structural categories emerged.

Similarly, AI doesn't just make existing organizations more efficient. It makes new organizational forms possible:

- Micro-enterprises at scale: 10-person companies with 1,000-agent workforces. The Hollow Firm pattern, but intentional.

- Continuous operations: Agents work while humans sleep. Zhao's "queuing tasks before bed" becomes organizational design.

- Flat hierarchies: Middle management exists largely for coordination and information routing. Agents can handle both. Hierarchy flattens.

The firms that understand this will build differently. The firms that bolt agents onto existing org charts will get the same modest productivity gains as factory owners who swapped waterwheels for steam engines but kept everything else the same.

Not Tokyo. City-States.

Zhao ends with a metaphor that deserves closer examination.

Pre-industrial cities were human-scaled. You could walk across Florence in forty minutes. Then steel and steam made megacities possible—Tokyo, Chongqing, Dallas. Zhao thinks the knowledge economy will follow the same arc: human-scale teams become agent-augmented thousands, human-paced workflows become continuous operations.

”"We lose some legibility. We gain scale and speed."

But here's where the verification thesis changes the picture.

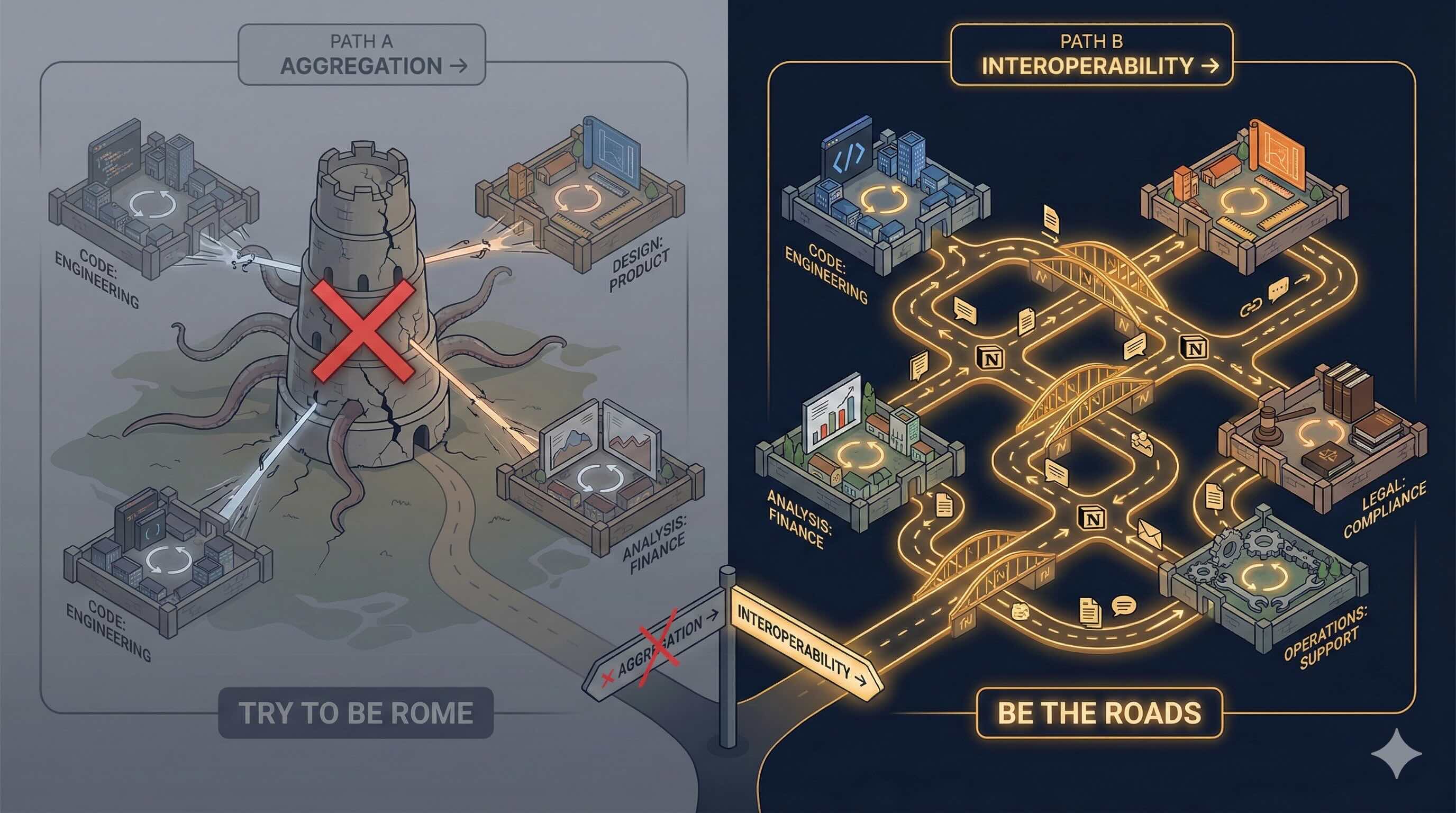

If verification were generalizable—if there were a universal way to test "is this knowledge work good?"—then Zhao's metaphor would hold. The knowledge economy would consolidate into megacities. One or two horizontal aggregators would capture the context layer, just as Google captured search and Facebook captured social.

But verification is domain-specific. Legal work has citations. Medical work has clinical standards. Code has tests. General knowledge work has... human judgment. No universal test. No single aggregation point.

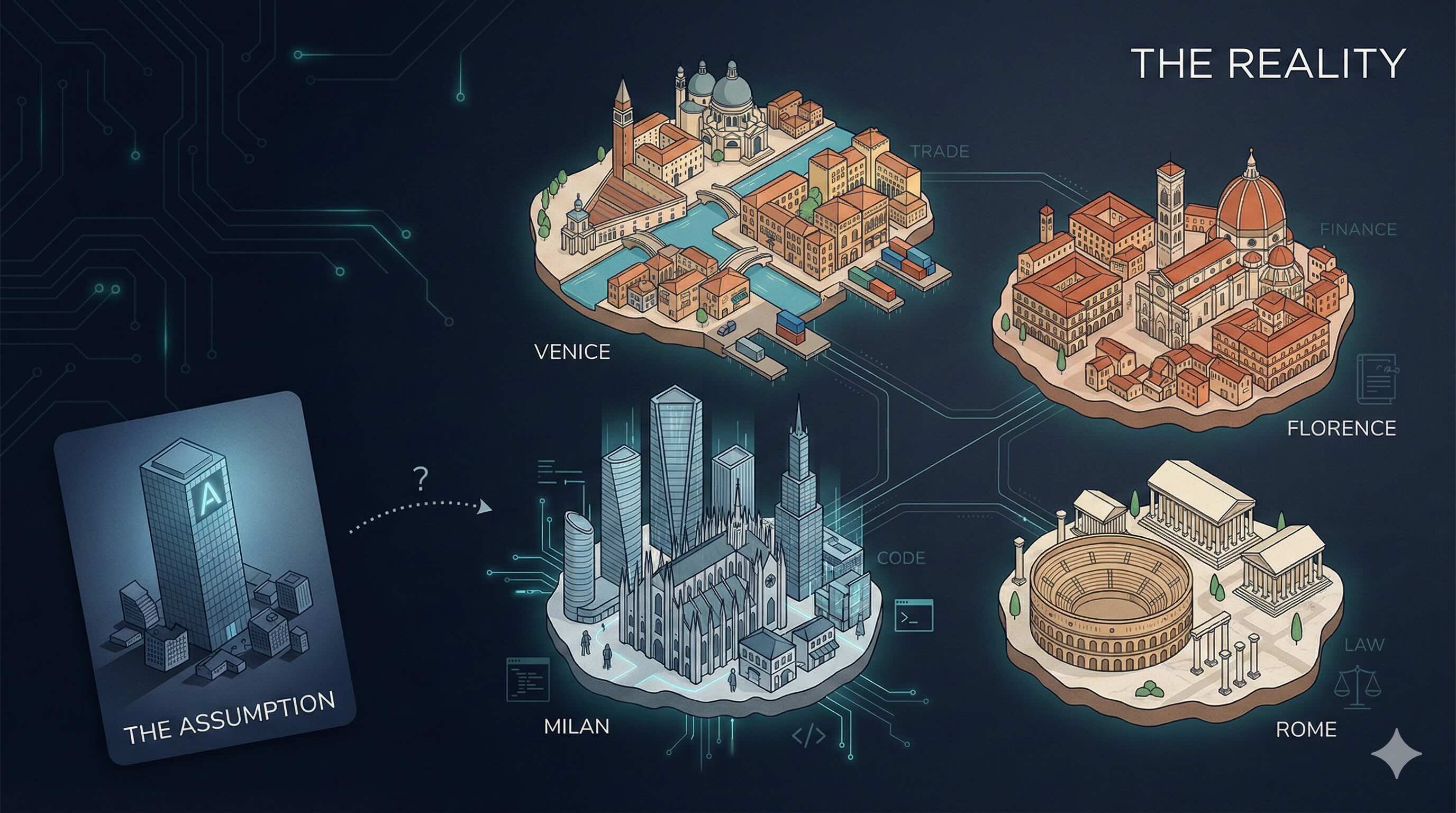

Which means the better historical metaphor isn't Florence → Tokyo.

It's Florence → Venice → Milan → Rome.

City-states. The Renaissance wasn't centralization into one megacity. It was specialized polities competing and cooperating. Florence for banking. Venice for trade. Milan for arms. Rome for religion. Each city had its domain, its expertise, its verification mechanisms. No single empire unified them.

The AI-augmented knowledge economy may look the same. Harvey owns legal. Abridge owns healthcare. Specialized players capture every domain that can define what "good" looks like. Not one skyline. An archipelago.

For the governance implications of fragmented AI empires, see Agent Governance Gap.

Where Aggregation Theory Breaks

This is where I depart from the standard Stratechery playbook.

Aggregation Theory predicts one winner. The aggregator captures the demand-side relationship, commoditizes suppliers, and extracts value from both sides. Google did it to websites. Facebook did it to publishers. The framework assumes a single aggregation point.

But what if there is no aggregation point?

For AI agents, the aggregation point would be whoever solves context + verification at scale. But if verification is structurally domain-specific—if there's no universal "is this good?" test for knowledge work—then no horizontal player can fully aggregate the market.

Each vertical that can define verification becomes its own aggregator. Harvey aggregates legal. Abridge aggregates healthcare. The market fragments into city-states, each with their own context layer, each with their own verification loop.

Aggregation Theory doesn't predict this. It predicts consolidation. But the domain-specificity of verification may be a structural constraint that prevents consolidation from occurring.

This isn't "verticals win." It's "there is no single winner." The AI agent market may be structurally resistant to aggregation in the way previous tech markets were not.

The Notion Pivot

If this thesis is right, Notion's current strategy is structurally challenged.

Zhao is betting Notion can be the horizontal aggregator—own the document layer, own the context, own the agent value chain. But if verification fragments, there's no horizontal aggregation to capture. Notion would be trying to be Rome in a market that wants city-states.

There's a pivot available, though.

Notion could win by being the interoperability layer between vertical empires. Not the aggregator. The protocol. The roads between city-states, not the capital that rules them.

This is actually closer to what Notion already is—a flexible substrate that connects to everything, integrates with every tool, serves every workflow. The 700 agents aren't the strategy. The integrations are.

The strategic implication: Notion should lean into interoperability, not fight for aggregation. Build the best connections to Harvey, to Abridge, to every vertical agent platform. Become the connective tissue that lets enterprises orchestrate across fragmented AI empires.

That's a different company than "the horizontal AI platform." But it might be the company that wins.

The Therefore

Aggregation Theory predicts one winner. But verification is domain-specific, and that breaks the theory.

There is no universal test for "is this knowledge work good?" Legal citations can be checked. Medical notes can be validated. Code can be tested. But strategy memos, project plans, marketing copy—these require human judgment. No objective verification. No aggregation point.

Which means the AI agent market doesn't consolidate. It fragments into vertical city-states:

- Harvey for law

- Abridge for healthcare

- Specialized players for every domain that can define quality

Each vertical owns its context layer, its verification loop, its autonomous agents.

The horizontal players—Notion, Microsoft, Google—face a structural problem. They can unify context, but they can't solve verification. Their agents will always need humans in the loop for general work. The verticals can remove humans because they've defined what "good" means within their domain.

Zhao's 700 agents are impressive. But they're impressive in the way early steam engines were impressive—significant, but not yet the transformation. The transformation comes when agents run unsupervised. And that requires verification that general knowledge work cannot provide.

The infinite minds future isn't one skyline. It's an archipelago.

”Not Tokyo. Not Rome. City-states as far as the eye can see, each specialized, each sovereign, none interoperable. The Renaissance, not the Empire.

Steel. Steam. Infinite minds. The next era won't be built by whoever aggregates the most. It'll be built by whoever verifies the best—domain by domain, city-state by city-state, until the archipelago covers the world.

Vertical Agents Are Eating Horizontal Agents

Harvey ($8B), Cursor ($29B), Abridge ($2.5B): vertical agents are winning. The "do anything" agent was a transitional form—enterprises buy solutions, not intelligence.

The Context Crisis: What to Do When Your Agent Runs Out of Room

Beyond RAG—the physics, strategies, and production patterns for managing context when 200K tokens still isn't enough.

Harvey: The $8B Legal AI That BigLaw Actually Trusts

How Harvey became the category-defining legal AI by solving what ChatGPT couldn't: data privacy through the Vault, 0.2% hallucination rate through citation-backed generation, and workflow integration at 4,000-lawyer firms. The definitive case for vertical AI.

The Hollow Firm 2.0: What Happens When Juniors Disappear

AI is automating junior work in law, consulting, and finance. Short-term margin expansion, but a 2035 succession crisis when AI-trained juniors become senior experts.